Featured Articles

Black-holes growing through mergers: Unraveling the mysteries of supermassive black holes through high-performance simulations

Tanikawa Ataru (Center for Computational Sciences, University of Tsukuba)

Masayuki Umemura (Center for Computational Sciences, University of Tsukuba)

Abstract

Supermassive black holes (SMBH) have been observed in a large number of galaxies, but their origin and formation is still unkown. In the standard theory of galaxy formation, galaxies grow by successive mergers of smaller galaxies. If every galaxy had a black hole, then one could imagine that, after merging, a galaxy might end up with multiple black holes in the center, but this would be at odds with observations. We have used the FIRST Simulator at the Center for Computational Sciences, University of Tsukuba, to simulate for the first time in the world the gravitational n-body interactions and mergersof multiple black holes at the center of a galaxy taking into account general relativistic effects. Following the dynamics of initially 10 black holes and 500,000 star particles for over 100 Million years, we find that the black holes at the center of the galaxy continuously merge and grow. This is a milestone discovery that explains the origin of supermassive black holes. This work is published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

PreprintBackground

Supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies

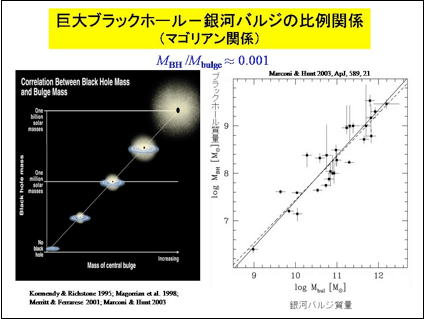

Recent observations indicate that most galaxies harbor a massive central black hole of around 10 Million to over 1 Billion times the mass of the sun. Furthermore, the mass of the central black hole is known to correlate with the mass of the bulge component of the host galaxy, with a constant ratio of roughly 1 to 1000 (see Figure 1). This relation is known as the Magorrian relation. The origin of this relation is not well understood.

Galaxy formation and black holes

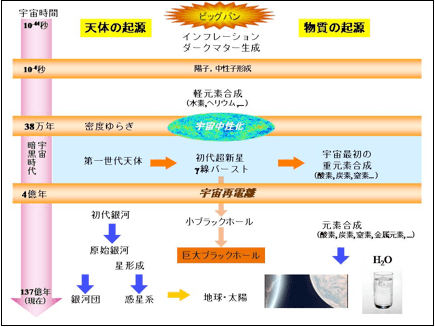

In the current cosmological paradigm of galaxy formation, the density fluctuations in the post-big bang universe magnified and collapsed to form bigger and bigger objects. Stars then galaxies. The first galaxies were fromed over 13.5 billion years ago from mergers of small galaxies (Figure 3). If each of the galaxies had a black hole with a mass according to the Magorrian relation, those black holes would be incorporated in the merged galaxy and wandering around the center. However, observations tell us that mostly only one supermassive black hole exists in the center of a galaxy, so the individual black holes must have merged, but a proper explanation for this is still lacking.

One of the major questions of supermassive black hole formation is in fact why there is only one black hole at the center of a galaxy.

The FIRST Project

To follow the evolution and merging of multiple massive black holes in the center of a galaxy, it is crucial to perform N-body simulations incorporating the effects of general relativity and ensuring very high-performance computing.

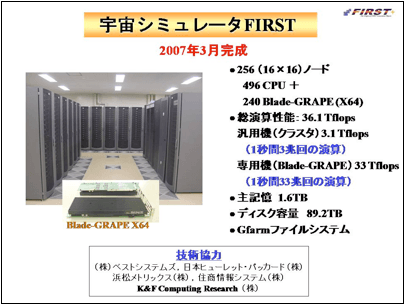

At the University of Tsukuba, we began the FIRST project in 2004, and completed the FIRST Simulator in 2009, a supercomputer designed to accelerate the numerical simulations of the formation of first stars, galaxies, and black holes. Figure 4.

The first Simulator uses Blade-GRAPE technology to calculate gravitational forces with high precision and speed, and posesses 256 computational nodes (496 CPUs) of which 240 nodes have Blade-GRAPE integrated. FIRST's peak performance is 36.1 TFlops (hosts: 3.1 TFlops, Blade-GRAPE: 33 TFlops). A hybrid parallel supercomputer such as this is a pioneering effort in world standards.. We have used the FIRST Simulatior to tackle the outstanding problems of supermassive black holes formation, and have found new results based on over a year of calculations.

Simulation Results

Using high-precision and high-speed simulations incorporating the effects of general relativity, we have solved the evolution of 10 black holes and 500,000 stars over 100 Million Years./

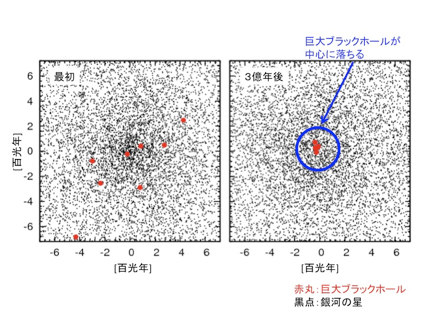

First, the massive black holes at the center of the galaxy lose kinetic energy through collective gravitational interactions with the many surrounding stars. This is called dynamical friction. As a result the black hole falls further toward center of the galaxy (Figure 5). The first two black holes that have fallen into the center will form a binary black-hole, orbiting each other. The binary black-hole will clear its surroundings of stars and will resume orbiting each other in a stable configuration, without merging. As this point, the formation of a supermassive black hole may seem unlikely. However, soon a third black hole will fall into the center and interact with the binary black-hole. The third black hole will take away a large chunk of orbital energy from the binary black-hole and the binary's separation is drastically reduced. Strong gravitational waves are emitted during this interaction and the black holes constituting the binary merge. This process repeates itself and the successive merger of black holes produces a supermassive black hole.

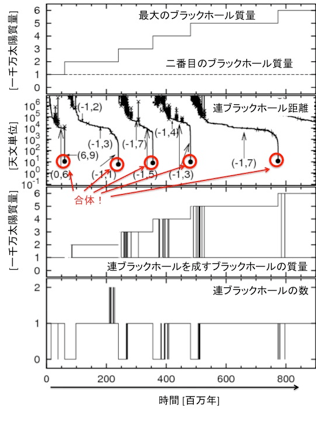

The most important results from our simulation are shown in the uppermost panel of Figure 6. A single supermassive black hole is formed from successive mergers of some of the 10 massive black holes. Not all of the 10 initial black holes have merged. From the second panel showing the binary distance as a function of time, one can see how the merging progresses. Black holes merge when their distances are reduced by more than 7 orders of magnitude.

Why does only one black hole keep growing? The second panel from the top of Figure 6 shows that a massive black hole remains in a binary state for quite a while before merging. Other black holes often interact with this binary but are never able to break it apart, and so the first binary created will always grow by successive mergers to the final supermassive black hole.

Furthermore, since interactions of a black hole with a binary black-hole imparts energy to the former, the former will have a harder time to form another binary (see Figure 6 bottom panel). Thus, our high-precision calculations revealed that it is only ever one black hole that keeps growing to a supermassive black hole, and it is always the largest black hole that keeps growing larger.

Our simulations follow the orbits of black holes up to the point that they can merge through the emission of gravitational waves, so the possibility of growth of black holes through mergers is proven without a doubt.

This is also the first high-precision and high-resolution simulation of multiple black hole mergers. There have previously been simulations of 2-3 black hole merger scenarios, but this is the first time anyone has shown that multiple black holes can merge to a supermassive black hole.

Summary

We have described our recent innovative results performing long-duration simulations with the high-precision high-speed FIRST Simulator. This result is a milestone in the understanding of the origin of supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies. Based on this research, new advances can be made in the theory of black hole formation since the early universe through cosmic time.

和 英

和 英