Featured Articles

The puzzling dark-matter of the Andromeda galaxy

Takanobu Kirihara (University of Tsukuba, Graduate School of Pure and Applied Sciences)

Yohei Miki (University of Tsukuba, CCS)

Masao Mori (University of Tsukuba, CCS)

Summary

The research group consisting of postdoctoral fellow Takanobu Kirihara of the Graduate School of Pure and Applied Sciences, CCS postdoctoral fellow Yohei Miki, and led by CCS associate professor Masao Mori, has probed the dark matter*1 surrounding the Andromeda Galaxy*2 and found that the distribution of the dark matter is significantly different to the that predicted by the standard models of cosmology and galaxy formation.

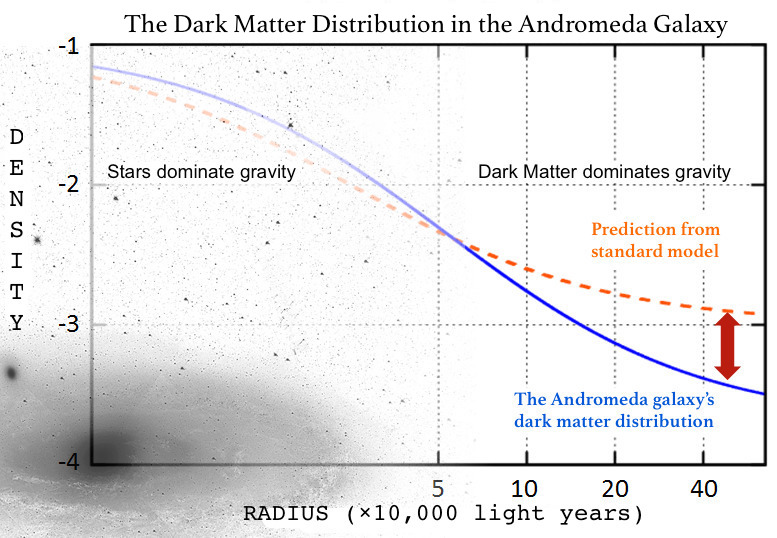

The Andromeda galaxy, at only 2.4 million light years away, displays clear signatures of a galaxy collision that occurred some 700 million years ago. In our research group, we have undertaken careful simulations of the galaxy collision using the supercomputers at the Center for Computational Sciences in order to examine the dark matter distribution surrounding the Andromeda Galaxy. From our simulations, we have reached the surprising conclusion, the first of its kind, that the dark matter distribution differs significantly from that predicted by the standard model. This conclusion implies not only the necessity of revising current cosmological galaxy formation theory*3, but also provides hints as to the nature of dark matter.

The results of this research are published in the Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan on December 10th, 2014, online version. (See also arXiv:1408.4920)

Motivation and background

In the current paradigm of cosmological galaxy formation, large galaxies come into being by repeated mergering through gravitational attraction of smaller galaxies. The backbone of this theory, the scaffolding that holds together the galaxies is the dark matter, which is also an essential part in the numerical simulations that aim to explain the origin of galaxies and galaxy clusters. The mass in dark matter around massive galaxies is typically 10 times the directly observable (luminous) mass of the galaxy, and the spatial extent of the dark matter is also roughly ten-fold the visible extent of the galaxy. Unitl now, many studies have determined the dark matter distribution in regions of high stellar densities in the inner regions of galaxies from the movement of stars, but measuring the dark matter distribution in the same way in the outermost regions of a galaxy where the stellar densities are extremely low, is still next to impossible, even with the most recent deep observations.

However, we know that galaxies have evolved by the repeated collision and merging of smaller galaxies. Even in our Milky Way, many relics of mergers have been discovered and observed in detail. In particular, we know from theory and observations that a satellite galaxy 1/400th of the mass of Andromeda collided with Andromeda about 700 million years ago. The collision resulted in a rod-shaped stellar stream 400,000 light years long and 20,000 light years wide, consisting of several 100s of millions of stars, emerging from the center of Andromeda, which is in fact observed. The key to understanding how the collision created the stream is the gravitational force of Andromeda that the small galaxy experienced while orbiting around Andromeda. The gravitational force exerted by a galaxy depends on its mass distribution, and since the dark matter carries most of the mass in the outer parts of the galaxy, the distribution of stars in the stream that resulted from the collision is sensitive to the distribution of dark matter. Conversely, by modelling the galaxy collision through numerical simulations and comparing with observations, we can pin down the dark matter distribution that gives the closest match to the observations.

Results

Takanobu Kirihara, Yohei Miki, and Masao Mori proposed that the relics of the galaxy collision that occurred in the Andromeda galaxy would provide a good probe of the outer dark matter distribution of the Andromeda galaxy. Using numerical simulations of the galaxy collision and the resulting giant stellar stream, they examined the dark matter density distribution in the outer regions of the Andromeda galaxy.

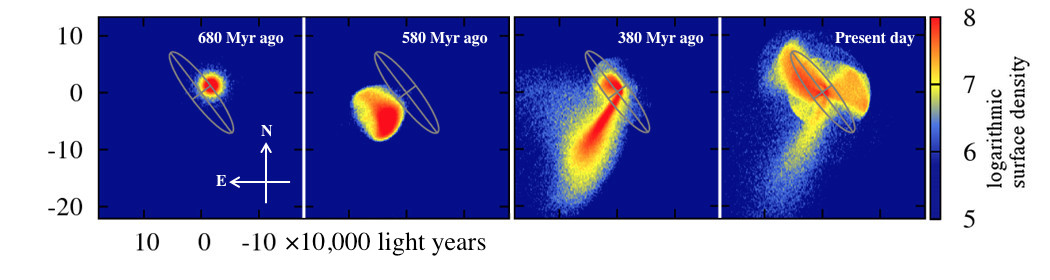

By representing the small satellite galaxy with approximately 250,000 particles and calculating the mutual gravitational forces of the particles as well as the gravity exerted by the Andromeda galaxy, they simulated the spreading of the stars during the collision over a time-span of 1 billion years (see first figure). By testing, among other parameters, 80 different distributions for the dark matter, we have, for the first time, established that the dark matter distribution, while matching the observations in the inner regions, fall off steeper and, thus, depart markedly from the theoretical distribution in the outer regions. This implies that some form of corrections need to be applied to the currently accepted standard theory of galaxy formation. Furthermore, this result may provide hints as to the nature of the dark matter particle. We may expect exciting future developments resulting from this research.

Future developments

Galaxy collisions like those that occured in the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy occur in all other massive galaxies. By combining high precision observations and large-scale numerical simulations, we can investigate the dark matter density distributions in other galaxies. Using this work as a stepping stone, further work may provide more evidence for the need to reform galaxy formation theory, and the theory of the nature of dark matter.

Footnotes

*1 While it has not been directly discovered as a particle yet, dark matter is an essential ingredient of the universe that holds together galaxies, and clusters of galaxies.

*2 The Andromeda Galaxy is the closest neighboring galaxy to our Milky Way, the galaxy we inhabit. The Andromeda Galaxy, like our Galaxy, possesses a large spiral disc.

*3 When our universe was born through the Big Bang, its density was almost uniform, but for small fluctuations. These fluctuations became gravitationally unstable and grew, and ultimately formed galaxies. The evolution of the density fluctuations to fully formed galaxies has been successfully simulated with self-gravitating dark matter particles in an expanding universe.

和 英

和 英